Nutrition Status of Children in Latin America Obesity Reviews

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Obesity is a public health problem worldwide, with a general tendency towards an increase in all countries from 2006 to 2016(1). In Latin America, obesity rates are amongst the highest in the world. In adults, rates vary as low as 19·7 % in Peru to every bit high as 28·9 % in Mexico, with generally higher rates in females (from 23·4 % in Paraguay to 32·8 % in United mexican states) compared with males (from xv·two % in Peru to 27·3 % in Argentine republic)(one). In 5–nine years old children, the prevalence rates vary from viii·vi % in Republic of colombia to as high equally 21·7 % in Argentina, with higher rates in boys (from 9·8 % in Colombia to 25·six % in Argentina) than in girls (from seven·4 % in Colombia to 17·8 % in Argentina)(one). In older children (ten–19 years), the prevalence rates vary from 6·1 % in Colombia to 14·4 % in Argentina, which higher rates among boys (from 6·3 % in Colombia to 18·3 % in Argentine republic) than girls (from 6·0 % in Colombia to xi·vii % in Mexico)(i). Concurrently, there are as well high rates of undernutrition (such as stunting and wasting) aslope overweight and obesity in Latin America, which is often referred to equally the double burden of malnutrition(Reference Jacoby, Tirado and Diazii).

Several efforts accept been designed and implemented in the region to address obesity. Because this is a topic of concern in Latin America, many of these strategies are contempo. Also, these take non been systematically reviewed by the level of the strategy, every bit suggested past the WHO guidelines to aid member states prevent obesity(iii–5). These guidelines emphasise integrated approaches and intersectoral collaboration to improve diet and increase the level of physical action(3). The WHO as well has the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable diseases(four) and the population-based approaches to forbid childhood obesity(5). Also, Pan-American Wellness Organization (PAHO) developed the Plan of Activity for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents(6).

These guidelines specifically emphasise the implementation of strategies from governmental structures to coordinate obesity prevention efforts, to the regulations or laws to back up healthy diets and promotion of concrete activity level, to the guidelines for the population for following and adopting good for you behaviours and to the level of population-wide or community-based programmes or initiatives. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the different strategies implemented in Latin America for obesity prevention. As well, this scoping review provides an overview of some of the results establish showing the impact of these strategies for addressing obesity in each land.

Methods

This scoping review was part of a broader project on Obesity and Diabetes in Latin America and the Caribbean sponsored past the Global Health Consortium at Florida International Academy. The national and regional strategies for obesity prevention were divided into four areas, as suggested by WHO guidelines on obesity prevention(3–5):

-

Governmental structures for obesity prevention. This refers to the types of structures in identify to support and enhance the obesity prevention strategies, which includes leadership (such as prime ministers, presidents and government ministers), funding dedicated to obesity prevention, monitoring and surveillance systems (such as nutrition surveillance, which has been traditionally divers as a system established to continuously monitor the nutritional status of a population using a variety of data drove methods, a key component to evaluate the effectiveness of the strategies implemented for obesity prevention), workforce capacity (such as skilled staff, training opportunities and quality preparation) and networks and partnerships (which refers to cantankerous-sectoral governance structures such every bit non-governmental organisations and private sectors involved in obesity prevention efforts).

-

Regulations to support salubrious behaviours. This refers to laws, regulations and policies written at the national level to back up healthy behaviours.

-

Guidelines for promoting good for you behaviours. This refers to specific recommendations for individuals to follow to achieve healthy lifestyles.

-

Population-wide or community-based programmes or initiatives. This refers to the specific programmes and initiatives at the local level to directly promote healthy behaviours.

Search strategy

A thorough search of obesity prevention strategies was done using Internet search engines and the country-specific governmental webpages in 2019. We specifically searched for these strategies in seventeen countries in South and Central America, excluding the Caribbean area as shown in Table one. Also, specific keywords were used for searching these strategies by the iv sections described above (Table 1). The search was not restricted by year, age groups or gender and we searched for documents in English language, Spanish and Portuguese. We too searched for reports from the WHO, the PAHO, FAO, Plant of Nutrition of Central America and Panama and UNICEF on general obesity prevention in Latin America. Central members of the Health Ministries in each country were contacted to obtain additional information well-nigh these strategies (those that responded to our emails are mentioned in the acknowledgement department).

Tabular array 1 Scoping review by keyword/due south search by strategy for obesity prevention in Latin America

To place the impact of these strategies for addressing obesity in the region, we did a literature search in PubMed, Agricola and CINAHL using a similar search as described in Table ane. Because of lack of data, the search was extended to Google and Google Scholar and other reports non published in these databases, such equally reports from PAHO. From the identified reports and studies, we too searched for additional references by hand.

Literature pick and data synthesis

We had a squad of five inquiry assistants searching for the information, each assigned to 2 or three countries. The team met with the chief investigator bi-monthly to talk over the search strategy and refined the search terms, every bit shown in Table one. A data extraction sheet was prepared, and this was used for all countries included. The search was done in stages; commencement, the dissimilar strategies implemented by each state for obesity prevention were searched; based on the results, the team prepared a preliminary listing of strategies identified. And so, based on this list, each banana searched again for these strategies in their assigned countries to check if that strategy was implemented by that land as well. If it had not been implemented, we also searched for news on legislation in the procedure of approving. Reports with information on several countries were shared among all team members to aid in the search process. The data extraction canvass was housed in a cloud service attainable to all members. The team was bilingual (English and Spanish) and for reports in Portuguese, the principal investigator review them or consulted some other person fluent in Portuguese.

Results

National and regional strategies for obesity prevention in Latin America

The strategies implemented at the country level in Latin America are described below.

Governmental structures for obesity prevention in Latin America

The following structures are created to support obesity prevention efforts:

Leadership: Most countries in Latin America define the Ministry of Health as the leading institution/agency for obesity prevention oversight. Still, simply 6 countries in the region have established a specific governmental role or committee specifically for obesity prevention efforts (Tabular array 2). Details of the names of each function or committee are establish in the online supplementary material.

Table 2 Governmental structures and national plans for obesity prevention in Latin American countries

Funding: Specific laws or mechanism to fund these efforts in Latin America was not evidenced in our review.

Monitoring systems: In Latin America, nutrition surveillance has been developed since 1977, but the type of system developed and implemented varies widely by state. A systematic review of official sources in Latin American and Caribbean countries found that 20-two had at least one nationally representative survey to monitor the nutritional status and among these, sixteen had at least ii surveys amid children(Reference Galicia, Grajeda and López De Romaña7). Our review found that all countries have a surveillance system in place and the types of surveys used to monitor the nutritional condition are shown in Tabular array 2. Details of each survey are found in the online supplementary material. In general, our review constitute that well-nigh surveys were conducted a few years ago. Current data are required to pattern appropriate interventions and measure their impact.

Workforce capacity: This was not evidenced in our review.

Networks and partnerships: Only a few countries reported this (data not shown); mostly with the Ministry of Education and Agronomics, academia and some non-governmental organisations such as WHO and PAHO.

National plans or policies for obesity prevention

At the country level, a national public health program with a multi-sectorial and life-course approach volition assistance guide all efforts implemented in each country. Currently, our review institute that 13 countries have obesity prevention plans/policies, and thirteen countries take a general policy to promote good for you dietary behaviours merely are non specific to obesity (Table ii). Details with the names of plans or policies are found in the online supplementary material.

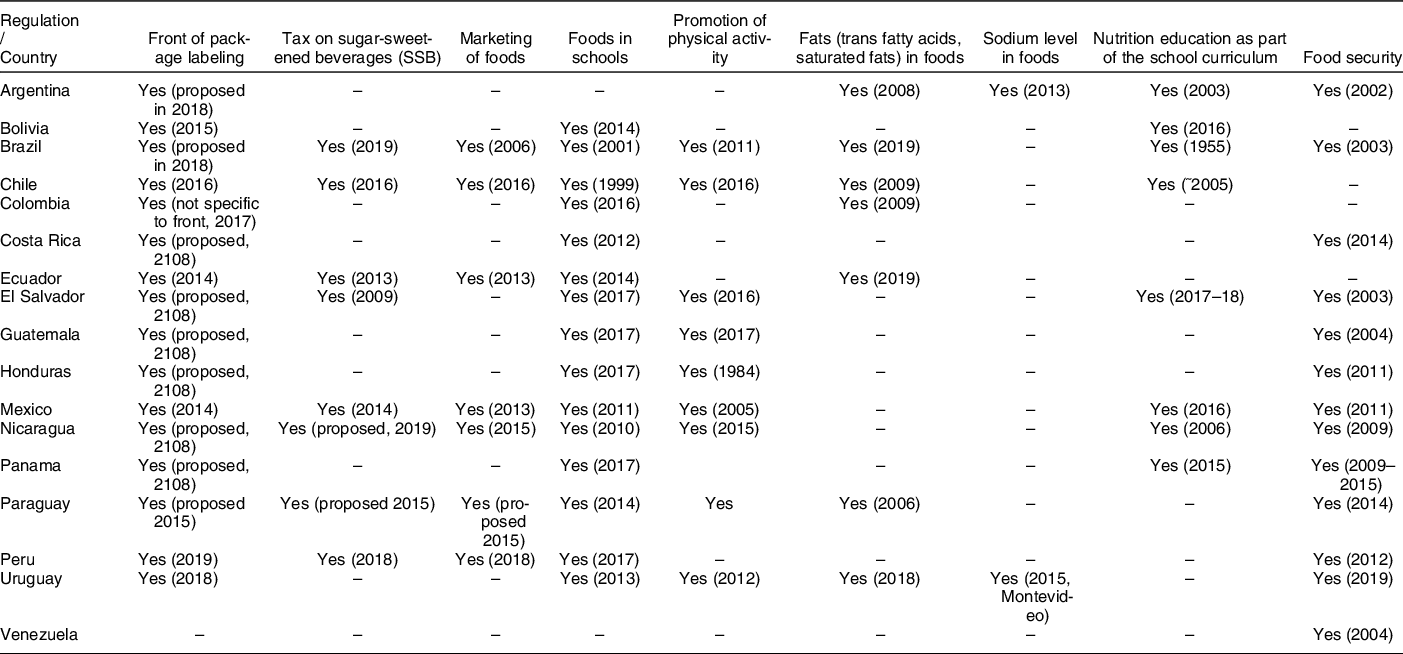

Regulations to support healthy diets

Many countries are planning or have implemented some of the policies and initiatives recommended by PAHO (Table 3). These include front end-of-bundle labelling (nine countries have proposed it and seven countries have implemented it), sugar-sweetened beverage (2 countries have proposed it and six countries accept implemented information technology), restrictions on fats (seven countries take in place restrictions on trans-fat acids and/or saturated fats), restrictions on Na level (two countries) or regulation of the school environment (fifteen countries). In improver, other regulations include regulation for the marketing of foods (one country has proposed it and six countries take implemented such regulation), regulations near nutrition didactics (ix countries) and near promoting concrete activity (ix countries) and regulations near food security (13 countries). Details of each regulation are found in the online supplementary textile.

Table three Regulations implemented or proposed in seventeen Latin American countries to back up healthy diets and concrete action

The information was non found for countries with (−). Details of each regulation are found in the online supplementary material.

Guidelines for promoting good for you behaviours

All countries evaluated have local dietary guidelines to translate global dietary guidelines into the cultural, preferences and characteristics of each population (Table 4). Also, ix countries have specific guidelines for children, six countries have guidelines for promoting physical activity and five countries accept other healthy behaviours guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of obesity and other chronic diseases (Table 4). Details of each guideline are plant in the online supplementary material.

Tabular array 4 Guidelines developed in seventeen Latin American countries to support healthy diets, physical activity and obesity treatment

The information was not found for countries with (−). Details of each program or initiative are found in the online supplementary material.

Population-wide or customs-based programmes or initiatives

Several programmes or initiatives accept been implemented in the countries reviewed (Table 5). These include school meal programmes to provide healthy breakfast, lunch and/or snacks to children at schools (seventeen countries), to promote nutrition instruction (vi countries take this at the population level and 11 at the school level), to promote physical activity such as cycle routes or Ciclovías (nine countries), to support family agronomics (iv countries), to promote healthier environments (three countries have this at the population level and 7 at the school level) and to care for obesity (four countries). Details of each plan or initiative are institute in the online supplementary material.

Table five Population-broad or community-based programmes or initiatives in seventeen Latin American countries to back up salubrious diets, physical activity and obesity prevention

There may exist other interventions or strategies not mentioned in this review that were either not published or easily accessible through an online search.

Information technology is of import to note that some of the strategies mentioned in this report may exist out of engagement or non being used by the time of this publication, equally these may accept changed if political changes occurred in the government.

Evidence on the evaluation of the impact of strategies implemented in these countries for obesity prevention

In general, our literature review evidenced a lack of reports and studies evaluating the strategies mentioned in the previous section. Nosotros study here the studies/reports plant by strategy.

At the level of obesity strategic plans, in 2014, all countries in Latin America signed the Program of Activeness for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents(vi,viii) . This plan adopts a preventive, multi-sectorial and life-class arroyo and considers the social determinants of health. Information technology aims at promoting an environment that is conducive to healthy eating and a higher concrete activity level and making the healthier option the easier option. To support countries in the fight against obesity, PAHO provides technical guidelines and cooperation, advocates for programmes and policies and fosters collaboration amid countries. Besides PAHO has other documents to assist member states in this endeavour(9). Also, the Council of Ministries of Health in Cardinal America developed the Plan for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents in 2014–2025(ten). In 2015, a meeting in Panama with experts from Healthy Latin America Coalition, PAHO/WHO, the Ministry of Health of Panama, and others discussed the need for a stronger part of the civil society in supporting and promoting policies on food, tobacco, booze and level of concrete activity in the region(eleven). In 2016, the Caribbean Public Wellness Agency and PAHO in collaboration with the Ministries of Health from countries with successful obesity prevention policies, such equally Mexico and Republic of chile, adult a roadmap to forestall childhood obesity(12). This is of import as lessons learned from efforts that have or accept not worked in different countries should be shared. In addition, multi-national studies tin provide rich information and insights into how unlike strategies work with different cultures, ethnic backgrounds, environments, etc. Too, the Non-Catching Diseases Alliance developed a Civil Club Action Program for 2017–2021 on Preventing Childhood Obesity in the Caribbean area(thirteen). Lastly, several institutions accept convened experts from PAHO, FAO and the National Institutes of Wellness's Fogarty International Middle(Reference Caballero, Vorkoper and Anandfourteen) to evaluate the situation.

At the level of nutritional policies, there are a few successful strategies in terms of acceptance, reach or effectiveness in changing behaviours in Latin America that should be discussed:

Front-of-packet label: At the Coming together of Ministers of Health of Central America in 2017, a proposed resolution to plant a front-of-packet organization for nutritional warnings was endorsed(15). Also, in 2018, the Ministers of Health of MERCOSUR (the Southern Common Market) agreed on a set up of principles to promote compulsory front-of-package labelling systems to indicate excessive sugar, Na and/or fat content(xvi). A study evaluating different labels pattern for front-of-package labels in m participants from all twelve countries participants of MERCOSUR in 2018 found that the modify in labelling significantly improved the power of individuals to rank products according to their nutritional quality(Reference Egnell, Talati and Hercberg17). As well, a study in Republic of chile done 6 months afterward the implementation of this regulation plant that 67 % of participants selected products with fewer warnings in the label and that the presence of 'high in' stamps influenced the purchase decision amongst 90 %(xviii). Also, information technology has been estimated that nutrient companies have modified one of every 5 products to make it healthier (2015–2016)(Reference Boza, Guerrero and Barreda19). In Ecuador, a study conducted a 1-twelvemonth mail service-implementation of this strategy (2015) found that it was widely recognised and understood(Reference Díaz, Veliz and Rivas-Mariño20). In two supermarkets in Quito among seventy-three participants, 88 % reported knowing about this arrangement and 28 % used it, which showed that it significantly influenced their shopping(Reference Teran, Hernandez and Freire21). In Mexico, a survey among parents of children in uncomplicated schools found that 51 % used the displayed nutrient content and reported to adopt the new traffic light system compared with the traditional organization(22). In Uruguay, a study found that 95 % of respondents saw the front of package labelling police as positive, regardless of age, gender or socio-economic status(Reference Ares, Aschemann-Witzel and Curutchet23). A greater percentage of individuals from low socio-economical groups (xc %) said the characterization would help them improve the quality of their diets, compared with those with a medium (86 %) and loftier (84 %) socio-economic status(Reference Ares, Aschemann-Witzel and Curutchet23). The bear witness on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered medium equally at that place is limited testify from studies in different countries and most have non included a representative sample of the population.

Saccharide-sweetened beverages taxation: A recent review focused merely on Latin American countries found that at to the lowest degree thirty-nine sugar-sweetened beverage regulatory initiatives have been adapted(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). From these, twenty-eight regulatory initiatives were passed by legislative and executive bodies and 11 are self-regulatory initiatives by the beverage industries. Also, 86 % of regulations past the government are binding; 56 % describe how to monitor and evaluate this, 62 % call for specific sanctions and 20 three specify who the body in accuse of this monitoring. In Chile, a sugar-sweetened beverage with more than 6·25 g of carbohydrate per 100 ml is taxed at xviii %, while carbohydrate-sweetened beverage below this threshold is taxed at 10 %. In Ecuador, a revenue enhancement of USD 0·xviii/100 grand sugar on carbohydrate-sweetened beverages with more than than 25 g of carbohydrate per liter. In Mexico, the revenue enhancement is 1 peso (which is well-nigh 0·05 USD) per liter and also an viii % taxation on snacks with more than than 275 kcal per 100 one thousand. In Peru, a tax of 50 % is imposed on beverages with more than 6 m per 100 ml. In Brazil, El Salvador and Nicaragua, this is at the proposal phase. In Colombia and Argentina, the strong industry lobbying impeded its implementation. The experience of Mexico and Chile is the virtually studied so far, as this was implemented a few years ago (2014 in Mexico and 2016 in Chile). In Chile, the results showed that there was a highly significant 22 % subtract in the monthly purchased volume of the higher-taxed, sugary soft drinks(Reference Nakamura, Mirelman and Cuadrado25). The reduction in soft drink purchasing was about evident amidst higher socio-economical groups and higher pretax purchasers of sugary soft drinks. In Mexico, taxed beverages purchases decreased from 200 ml/d at the finish of 2013 (just earlier the implementation of the beverage taxation) to about 160 mg/d at the end of 2014 (after virtually 1 yr of the tax implementation), which represents a refuse of 12 %(Reference Colchero, Rivera-Dommarco and Popkin26,Reference Colchero, Popkin and Rivera27) . Reductions were higher among the households of low socioeconomic condition (17 % decrease by the terminate of 2014 compared with pretax trends). Also, purchases of untaxed beverages were 4 % (36 ml/capita/d) higher, mainly driven by water. The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered medium as in that location is limited evidence from studies in different countries and virtually have not included a representative sample of the population.

Regulation for the marketing of foods: These initiatives have varied widely by country, with some having formulated guidance, while other restrictions, with some sanctions, merely most practice not have a articulate clarification of their monitoring. Banning unhealthy food ad may have a positive impact on children's diets. A review in Brazil showed that most studies were based on constabulary analysis or qualitative written report of advertisement, and several companies had differences in ethical behaviour regarding food advertisements, showing a lack of delivery to the policies on food advertisements(Reference Kassahara and Sarti28). Then far, Chile is the country that has implemented the nearly comprehensive regulation of food publicity, regulating 35–45 % of candy foods and beverages high in added carbohydrate, Na or saturated fat. Also, there is a ban on the marketing of certain unhealthy foods during selected child Idiot box programmes. In United mexican states, the regulation prohibits advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages to children mainly in TV or flick theatres, with some exceptions for sure programmes. Brazil limits all publicity targeting nutrient for children. Republic of bolivia, Chile and Mexico also require to include messages to promote healthy lifestyles, and Brazil, Chile, Republic of ecuador, Mexico and Peru require the inclusion of warning messages most the potential health effects of sure products(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). Republic of ecuador and Nicaragua are at the proposal phase to implement it, while in Argentina, it was vetoed by the President(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). In Mexico, an analysis of children'south advertisements in 2012–2013 in the nearly pop public TV showed that about 75 % of the total food and beverage advertisements were aimed directly or indirectly at children(Reference Théodore, Tolentino-Mayo and Hernández-Zenil29). Even amidst companies that had signed the cocky-regulation, more than than 31 % of the advertising of unhealthy products were aimed at children or adolescents. A review of twenty-3 studies (six in Chile, 5 in Mexico, four in Brazil, three amongst Hispanics in the The states and one in Argentina, Republic of peru, Republic of colombia, Honduras and Venezuela) about food advertising directed to children on TV found a loftier exposure of TV food advertised for children and their family, which has been associated with preference and buy of unhealthy foods and with overweight and obesity(Reference Bacardí-Gascón and Jiménez-Cruz30). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is also considered medium.

School repast programmes: But a few studies are evaluating the effectiveness of schoolhouse-based programmes. For example, in Brazil, a study of 20-one public schools in one region in 2014 found that virtually 31 % of children were overweight, that breakfast and snacks were equanimous of 68 % of ultra-processed foods, while 92 % of the tiffin foods were unprocessed and minimally processed foods(Reference Batista, Mondini and Jaime31). In Colombia, children participating in the program may have ameliorate school performance(Reference Niny32). In Chile, this program has been shown to reduce school drop-out rates(Reference Villena33). In Mexico, the regional programme 'Wellness to Learn (Salud para Aprender)' establish a decrease in overweight and obesity from 25 % in 2010–2011 to 19 % in 2016–2017 among preschoolers, from 32 % to 30 % in uncomplicated children and from 38 % to 34 % in adolescents(Reference Trejo Hérnandez and Raya Giorguli34). They likewise establish that the % of breakfast consumption increased from 84 % in 2010–2011 to 86 % in 2016–2017, consumption of fruits and vegetables iii–iv times per week increased from 34 % to 36 % and sedentarism improved past one–two points. In Peru, the Milk Glass Programme, which impacted 61 % of children 0–6 years and 18 % of children 7–13 years, establish that 63 % of those participating had a decreased hazard of obesity(Reference Diez-Canseco and Saavedra-Garcia35). A systematic review of twenty-1 studies (n 12 092) with different types of educational interventions in children (nutritional campaigns, physical activity level and ecology changes) in Latin America institute that mixed approaches combining nutritional campaigns, physical activity level promotion and ecology changes were the about constructive interventions(Reference Mancipe Navarrete, Garcia Villamil and Correa Bautista36). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is as well considered medium.

Regulation of the school environs: Irresolute the food environments can have a strong influence on the school-age population and could lead to changes in nutrient preferences and weight condition. These policies have been implemented in several countries as described previously, but they differed in their legislation and how strict they are. For example, in Brazil, Ecuador, Republic of chile, Republic of peru and Uruguay, the policies to limit saccharide-sweetened beverages in schools are through their legislative and executive, while in Costa Rica and United mexican states, this has been through executive decrees but, which may have a different touch(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). Although all are mandatory, some accept not specific sanctions if schools are non in compliance, such as in Ecuador. As well, some countries are very strict in the type of beverages banned. For instance, in Peru, drinks with more than 2·5 grand of sugar per 100 ml are not allowed, while in Republic of ecuador and Uruguay, the limit is on beverages with more than seven·5 thou of saccharide per 100 ml and in Mexico near all beverages that provide calories are banned, except on Fridays(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). Therefore, most legislations allow 100 % fruit juices, which can still add together to the total calories consumed per day, except for United mexican states. Also, this legislation is mostly for public schools and at the uncomplicated level. Although there are no results bachelor yet on their impact on reducing obesity, there are a few obstacles encountered in their implementation. For example, in Mexico, the food industry has shown strong opposition, which delayed the process(Reference Charvel, Cobo and Hernández-Ávila37). Also, studies in United mexican states institute that the schools lacked the space, nutrient condom measures or the structure to implement these policies(Reference Gallegos Gallegos, Barragan Lizama and Hurtado Barba38). They also lacked a strong strategy to implement this throughout and faced difficulty in irresolute culturally strong practices, among others(Reference Treviño Ronzón and Sánchez Pacheco39). The show on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered weak as there are very limited studies.

Programmes to promote physical activity: These include the modification of the school curriculum to increase concrete activity level, policies in urban planning to increase access to sidewalks and areas of recreation and concrete action, among others. A global review of the touch on of such policies on obesity found that individuals living in walkable communities, with access to parks and other recreational areas, with sports facilities or spaces for recreation in schools and greater admission to stairs, were all associated with higher levels of concrete activeness(Reference Sallis and Glanzforty). In Latin America, just a few studies are evaluating such programmes. In Republic of colombia, surveys conducted in 2009 constitute that individuals participating in the wheel route (Ciclovía) programme met the physical activity recommendation in leisure time (60 %), and most participants met it by cycling for transportation (71 %)(Reference Torres, Sarmiento and Stauber41). Another survey amongst current and former programme coordinators of lx-7 bike routes in 2014–2015 institute that the average number of participants per event was > forty 000 (forty–i 500 000) with an average length of 9·1 km (1–113·vi)(Reference Sarmiento, Díaz del Castillo and Triana42). The participation of minority populations was high (61·2 %). The electric current study also evaluated the sustainability and scaling-up of five programmes and they all met the most important factors for this, such every bit some level of government support, alliances, community appropriation, champions, organisational capacity, flexibility, perceived benefits and funding stability. All the same, at that place were several differences in their design, operations, political affiliations, funding and alliances, which may be important for the multifariousness and inclusion of different segments of the population. The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered weak as in that location are very express studies.

Efforts to reduce fatty or Na in foods: In Argentina, a law was enacted in 2013 to regulate the maximum Na levels in meat products, farinaceous foods and soups, bouillons, and dressings. If all these foods fully comply with this regulation, this would reduce Na intake by about 30 mg/d (Reference Elorriaga, Gutierrez and Romero43). In a study conducted in 2019, more than than 90 % of the nutrient products included in the national Na reduction police force in Argentina were found to be compliant(Reference Allemandi, Tiscornia and Guarnieri44). The show on the effectiveness of this strategy is besides considered weak.

Programmes to promote nutrition educational activity: In Republic of chile, the v-A-24-hour interval campaign was tested on an adult sample (northward 1897), finding later on ane year that recalls of the materials was high and that the proportion of people proverb that they consumed 3–4 servings a twenty-four hour period increased from 49 % to 51 %(Reference Vio, Albala and Kain45). Another written report in Chile found that 9 months later on the implementation of the Santiago Sano programme found that 22 % of the participants had improved their nutritional status(46). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is likewise considered weak.

Discussion

Our results establish that nigh countries defined the Ministry of Wellness as the lead institution for the oversight of obesity prevention strategies. Although all countries accept implemented a survey to monitor obesity, most surveys were done several years ago, with only a few countries with recent surveys. Well-nigh countries reviewed (thirteen out of seventeen countries) accept a national obesity prevention plan with published guidelines for following healthy diets. Also, eight countries have guidelines for increasing the level of physical action and other good for you behaviours. The most common regulations implemented/designed related to obesity prevention are front-of-packet labelling (xvi countries), nutrition instruction in schools (nine countries) and schoolhouse surround (fifteen countries). The most common community-based programmes related to obesity prevention are school meals (seventeen countries), nutrition teaching (fourteen countries) and complementary nutrition (eleven countries).

This scoping review besides provided an overview of the evaluation of these strategies. Although just a few have been evaluated, some had positive results. In item, those with positive results are the strategies that have a coordinated, multi-disciplinary and multi-sector arroyo considering aspects of behavioural change for improving diet and level of physical activity that involves parents and other community members. Obesity prevention efforts should have multidisciplinary approaches involving several sectors; therefore, their evaluation requires expertise in designing and evaluating complex interventions. These should include promoting diet and physical activity level integrated with the different environments and should evaluate how the multiple influences on behaviours and obesity operate differently in subgroups. Even so, many universities and inquiry institutions in Latin America take limitations for providing the preparation, resources and infrastructure(Reference Yavich and Báscolo47) necessary for these types of studies. Besides, funding for research is very limited and frequently rely on external funding and donors. Also, it is of import to evaluate if interventions in the healthcare system are a good approach for those that regularly have no access to this; these individuals may need another type of intervention. Also, these efforts must be regulated, with legislation and executive-level back up, which is key for their continuation in fourth dimension. Examples of some of the strategies that have shown positive results include front end-of-package labelling, school environs/repast regulations/programmes, food marketing regulation, beverage revenue enhancement and programmes to improve the level of physical action.

An important gap identified in this scoping is the lack of baseline data. This is key when evaluating the touch on of the different strategies implemented in each country. As shown in Table ii, many countries practice not implement regular surveys to monitor obesity. Furthermore, some of the strategies found seem to overlap with other programmes, and information technology was not clear from our search if all programmes described here were being implemented or were active. Some may have been discontinued without an evaluation process, or maybe they were evaluated but the results were not published. In some countries, the discontinuation may be due to a change of government, especially those without legislation. Also, although some programmes seem to be agile, some may non be receiving funds from the government; therefore, they may not be implemented as intended.

Many of the strategies described in this review are aimed at reducing nutrient insecurity every bit undernutrition has been traditionally more than prevalent in Latin America. The dual brunt of malnutrition(Reference Jacoby, Tirado and Diazii), in which undernutrition coexist with obesity, poses a major claiming in Latin America. The WHO proposed the double-duty actions to address this(48). Double-duty actions include interventions, programmes and policies that tin be implemented to simultaneously reduce the risk or brunt of both undernutrition and obesity. These could include programmes or strategies to protect and promote sectional breast-feeding, to optimise early on nutrition and maternal diet, school food policies and marketing regulations, such as the ones discussed in this review.

The strategies described here crave many resources and skills that are defective in Latin America. As well, the economic growth in the region in the past two decades has led to major socio-economical disparities, which may business relationship for a large variation in the obesity increase among women, particularly in Mexico(Reference Su, Esqueda and Li49). This economic growth has vastly changed the foods bachelor in the region, with a precipitous increase in high-energy processed foods, replacing the traditional foods consumed in nearly of these countries. This was evidenced in a sales analysis of ultra-processed products from different outlets in xiii Latin American countries in 2000–2013(50), which was associated with obesity. Information technology besides showed that processed foods sales steadily increased in most countries, particularly in urbanised areas and those opened to foreign investment and deregulated markets. This combination of factors has led to an environment that is not conducive to good for you behaviours.

On the other mitt, in Latin America, the engagement of different health professions and public institutions with multi-disciplinary settings is a strength when implementing obesity prevention measures. The food industry is yet to be engaged in these efforts, with only a few initiatives. Their low engagement could be related to the change of governments and rules and also possibly lack of ethical principles guiding public–private partnerships. With the increased sales of processed foods in urbanised areas in Latin America, they must get involved. Other sectors such as communications, economics and policy assay should also be included. This is fundamental as a multisector collaboration (government–academic–ceremonious guild–nutrient industry) is critical in identifying and conducting research and translating this evidence into programme and practice. This type of partnership, with well-divers and measurable goals and established ethical principles guiding their deportment, will lead to more than effective interventions. It volition also help the governments be improve informed of the efforts that are nearly effective based on enquiry and the limitations and improvements that must be implemented.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this scoping review is that it followed a systematic process to identify the different strategies implemented in Latin America. The search strategy was comprehensive, with the inclusion of reports and publications in Spanish, English language and Portuguese. Therefore, we believe that we captured the relevant information from all the unlike sources searched. A potential weakness of this scoping review was that some strategies may not have been published or the ones found may accept not been updated with the changes in government. Also, at that place were limited studies or reports found evaluating the affect of these strategies; too, some reports may have not been published yet as some of these strategies are very recent to have impact results. Besides, some countries may not have experts to interpret these results into a publishable peer-reviewed manuscript. Some reports could also be classified or not released to the public. Furthermore, the few studies with results on the impact of the identified strategies used different study designs, which was challenging when synthesising the results. Some studies included results about the number of individuals impacted, while others showed results on the improvement in dietary patterns and level of concrete activity. Near included just a relatively small-scale number of individuals, which limits the generalisability. Only one or two studies evaluated the long-term impact on obesity.

Determination

The Latin American countries included in this review accept been designing and implementing important public health programmes for obesity prevention, such as forepart-of-package labels, regulations and programmes for the school environment and to provide good for you meals, nutrient marketing regulations, sugar-sweetened beverages revenue enhancement and to promote the level of concrete activity. However, in that location is a need to evaluate programmes and initiatives, by gathering baseline information before these are implemented at the population level and evaluating their touch after implementation. Also, there is a demand to implement and continue successful combined programmes and policies that tackle both undernutrition and overweight. This information tin help appraise the deportment that tin can be generalised to other countries within the region and can help inform how to prevent obesity in different settings.

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/obesity-in-latin-america-a-scoping-review-of-public-health-prevention-strategies-and-an-overview-of-their-impact-on-obesity-prevention/87FA239B3D913EB2B72CEFDA94C711FC

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment